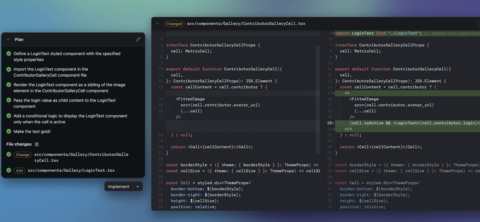

Earlier this year, GitLab unveiled Duo, a set of AI features that aim to help developers be more productive by summarizing issues and generating descriptions of epics and […]

GitHub teases Copilot enterprise plan that lets companies customize for their codebase

GitHub today announced plans for an enterprise subscription tier that will allow companies to fine-tune its Copilot pair-programmer based on their internal codebase. The news constituted part of […]

Online store exposed millions of Chinese citizen IDs

A security researcher said he discovered millions of Chinese citizen identity numbers spilling online after an e-commerce store left its database exposed to the internet. Viktor Markopoulos, a […]

Startups learn the hard way that relying on OpenAI’s tech can burn them

ChatGPT takes out a bunch of startups in one fell swoop Haje Jan Kamps 8 hours A recent update to OpenAI’s ChatGPT that allows users to upload PDFs […]

Tech layoffs return with a vengeance, Gaza internet collapses and Apple hosts a Halloween event

Hey, folks, welcome to Week in Review (WiR), TechCrunch’s regular newsletter covering the past week in happenings around the tech sphere. Winter’s finally arrived, judging by the NYC […]

If your startup doesn’t seem impossible at first, it’s not hard enough

Welcome to Startups Weekly. Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Friday. Startups exist to solve complex problems, not to be a quick moneymaking scheme, […]

‘How to Have Sex’ review: A brutally honest film about early sexual experiences

Molly Manning Walker’s directorial debut examines consent and sexual pressure, following three teens on an end-of-exams trip. Review.

Content warning: This review discusses sexual assault.

Despite its searchable title, How to Have Sex is by no means a tutorial.

It’s more of an intentionally vague concept that pervades Molly Manning Walker’s directorial debut, indicative of a more sinister knowledge gap affecting young people today when it comes to sexual experiences — thanks, inadequate sex education and rampant online misinformation!

One of the most important films of the year, How to Have Sex examines British youth culture, consent, and sexual pressure through three teens on their end-of-exams trip to Crete, Greece. Tacky pool parties, a bucketload of crappy booze, and formative experiences await, some thrilling, some deeply traumatic. With powerful performances from a talented, emotionally generous young cast, superb cinematography from Manning Walker, and a script that actually sounds like teen conversation, How to Have Sex is a triumph of honest storytelling.

It’s by no means an easy watch, nor should it be. But it’s reality.

What is How to Have Sex about?

When you’re finished exams at the end of high school and you’re faced with impending results, the possibilities of the future, and the newfound independence that comes with graduation, what do you do? You grab your two best friends and head to Greece, geared up for a week of too many shots, too many spews, too many trays of cheesy chips, and doing it all again night after night. You’re set to make hilarious, gorgeous memories with your mates, and meet some new faces. And it’s going to be the “best holiday ever”.

Until it’s not.

This is the set-up for Manning Walker’s film, which sees 16-year-old Tara (Mia McKenna-Bruce), Em (Enva Lewis), and Skye (Lara Peake) heading to a week of partying in the coastal town of Malia for the British equivalent of America’s Spring Break or Australia’s Schoolies. The horizon is clear: drinking, dancing, and sex. For Tara, she’s yet to have her first sexual experience and she’s feeling under pressure to “catch up” with her friends. When Tara meets the neighbours, their week of partying intensifies and the pressure rises. However, for Tara, her first sexual experiences aren’t respectful, wanted, or consensual, and the film follows her during the week processing what’s happened as the party rages on.

How to Have Sex navigates consent and assault with respect and honesty

How to Have Sex isn’t the first teen film to examine these experiences of sexual assault and consent by any means, but Manning Walker brings a brutal honesty and frankness that sets the film apart. Through superb scripting and performances, the film acknowledges how male violence is normalised or brushed aside, how that “nightmare of a guy” in a social circle known for misconduct is simply allowed to carry on because “I’ve known him since we were little.” And in particular, the film puts emphasis on peer pressure to say nothing — and how blatantly society puts this responsibility on survivors.

You should have said something. These conversations aren’t plucked from obscurity, I’ve heard them myself. You might have heard them.

“You should have said something,” Tara is told. You should have said something. These conversations aren’t plucked from obscurity, I’ve heard them myself. You might have heard them. Manning Walker told the BFI that the idea for the film itself came from a similar trip in her own adolescence, but particularly from speaking to a group of friends years later about their collective experiences, and recognising yeah, that wasn’t OK. The film shows how casually teens can feel pressured into unwanted sexual experiences, even celebrated for doing so. And it’s this level of authenticity in the script that imbues How to Have Sex with uncomfortable accuracy, reminding us that not every teen sexual experience is as wacky as other films and TV shows present them.

Not everyone will feel this way. When I saw the film at the BFI, I was shocked to sit behind two people on the bus who loudly debated the incredulity of Tara’s circumstances, that her friends would never act as they do, that this kind of assault would never happen, and that Tara’s eventual courage to speak up about her experience felt removed from reality. I cannot disagree with these opinions more (and I tried my best to not scream these in public, I’ll tell you what). Toxic friendships that hasten sexual experiences and leave people in vulnerable scenarios exist. Everyday social circumstances that enable predatory behaviour exist.

Survivors of sexual assault do not always have the words to describe what has happened, nor should others blame them for processing it at their own pace. It’s a shocking reality that many who experience sexual assault may not feel able to label it as such, and misguided perceptions of rape keep this confusion in a deeply dangerous ‘grey area’.

“The way our culture talks about and defines rape can have significant impact on a person’s ability to recognise when it has happened to them,” Mashable’s Rachel Thompson writes in her book Rough. “The stigma attached to rape and cultural ideas about the consequences of accusing someone of sexual violence also present obstacles in acknowledging the reality of a violation.”

Toxic friendships that hasten sexual experiences and leave people in vulnerable scenarios exist. Everyday social circumstances that enable predatory behaviour exist.

Thompson points to shocking figures from the End Violence Against Women coalition, writing: “33 percent of people in Britain think it isn’t rape if a woman is pressure into having sex but there’s no physical violence. And one in ten people are ‘unsure or think it’s usually not rape to have sex with a woman who is asleep or too drunk to consent.'”

It’s this data and this reality that trickles into casual conversations and sexual experiences in How to Have Sex, how the characters talk about and pursue sex without speaking to consent or feelings of pressure in vulnerable circumstances.

How to Have Sex features an impeccable young cast

As the film’s protagonist, McKenna-Bruce takes Tara through a deeply compelling and devastating arc, beginning as a joyful, hilarious girl, the absolute life of the party, and finding herself crushed by her experiences of alienation, peer pressure, and ultimately, surviving assault. Through lengthy close ups that muddle the surrounding sounds, Manning Walker allows McKenna Bruce to move Tara through a mix of emotion — shock, shame, anger, disappointment, fear, suppressed vulnerability — as the party rages on around her. As much as she tries to plunge herself into every dance floor and pool party, Tara appears disconnected from everything: her social group, the ludicrous sexual stunts that define the Malia parties, and especially her own body.

Meanwhile, Tara’s two best friends prove polar opposites, with Peake perfecting peer pressure queen Skye and Lewis bringing sweet, hilarious nuance to Em, who actually recognises something is wrong with her friend. Both Skye and Em fail to adequately handle Tara’s experience, both painfully championing her in their own way instead of checking in properly with her. But what Manning Walker does with the core three is distill an absolute lack of knowledge each of them has about sex, consent, and pressure. They literally do not have the language to talk about their experiences beyond verbal high-fives, and because of this, Tara’s pain goes unacknowledged by her friends until the very last moments.

The film proves the best part of any party is before it’s started

If there’s a dominant truth in How to Have Sex it’s that the best part of the party is in the promise of it all. When Tara, Skye, and Em arrive in Malia, they’re giggling, bickering, screaming, and splashing about in the freezing ocean, on top of the world. They’re enamoured with their tiny hotel room, praising “the best view I’ve ever seen in my life”.

Though Manning Walker knows how to shoot the hell out of a party scene, it’s these early moments that I clung to for the rest of the film, the trio embracing their independence with hands in the air, deep-and-meaningfuls in the street while stuffing their faces with chips, and stocking up on supplies in the supermarket with their hard-saved cash. It’s pure, adolescent bliss, on the cusp of adulthood, and it’s truly fun to watch the chemistry of the core cast, imbuing Tara, Em, and Skye with sheer resilience, taking another shot right after a cheeky spew. They’re ridiculous, silly, and hilarious, and completely avoiding thinking about the future.

It’s this joy and silliness they deserve, but the formative experiences ahead of them will determine the rest of their lives. When the credits rolled of How to Have Sex in my screening, the cinema filled with the enormous, emotive sounds of “Strong” by Fred again… and Romy. I couldn’t move. It was perfect. “You don’t have to be so strong,” Romy sings. And she’s right. But we are.

If you have experienced sexual abuse, call the free, confidential National Sexual Assault hotline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673), or access the 24-7 help online by visiting online.rainn.org.

‘Sly’ review: A Stallone documentary that plays like a ‘Rocky’ sequel`

Netflix’s documentary “Sly,” about Sylvester Stallone, plays like a “Rocky” sequel.

For about its first hour, Sylvester Stallone documentary Sly (directed by Thom Zimny) unfolds with surprising dexterity, journeying across the actor/filmmaker’s early life through the lens of his most iconic roles. Both its subject matter and aesthetic approach make it an effective work of introspection and artistic critique on the surface, even though it eventually loses focus. Playing at times like a missing Rocky documentary, Sly avoids the emotionally thorny material it might otherwise have been able to mine were it not so reverential towards its central star.

It’s the rare documentary feature that might have benefitted from being a longer series, but at 96 minutes in length, it establishes an adequate baseline for those in search of a quick Stallone 101. Talking heads include the actor, his brother Frank, his longtime collaborator John Herzfeld, and various heavy Hollywood hitters, from ’80s rival Arnold Schwarzenegger to Quentin Tarantino.

This patchwork of interviewees seeks to answer the question of who Sylvester Stallone is, even though the subject and the film itself seem rather convinced they have the answer. It’s a look back at a lengthy career and 77 years of life, expanding on key moments of success while brushing uglier elements of the rug. It borders on hagiographical self-promotion — Stallone is an executive producer on the movie, after all — but the way it shines a light on his creative process is entirely worthwhile.

What is Sly about?

Credit: Netflix

At its outset, Sly offers the appearance of Stallone’s life having come full circle in a meaningful way, as he packs up his lavish Malibu mansion filled with Hollywood memorabilia and plans to move back East. Before his skyrocketing success from writing and starring in Rocky in 1976, Stallone grew up in New York’s rough-and-tumble Hell’s Kitchen, an oral picture of which he paints vividly as he revisits the neighborhood’s now-pristine streets.

Spread between two cities, this narrative framework not only allows Stallone to reflect on people and places from his past, but it also lets Zimny zero in on various statues, action figures and privately commissioned lifelike busts of iconic Stallone characters, including Rocky in his victory pose, as a means to introduce the story of each fictitious avatar through their popular iconography. From there on out, Stallone dives back into tales from his childhood, from growing up with a violent and withholding father, to struggling to be seen as anything more than a talentless lug during his early career.

Stallone, whose obliquely framed, often shaky close-ups make up most of the film, carries himself with a remarkable self-awareness about his limitations, and an equally remarkable critical intellect about what the audience takes away from each of his pictures, and where some of them might have failed. By presenting Rocky Balboa and John Rambo through a psychoanalytical framework, he gives these cinematic heroes their due as more than just hulking ’80s icons; to him, they’re extensions of himself and his father, respectively. Granted, this feels like a conclusion that Sly may have been able to articulate by skillfully building towards as it explored Stallone’s history. Instead, the film leaves little room to uncover emotional mysteries, presenting them instead as thudding and obvious conclusions up front, as articulated by Stallone himself.

The effect of this narrative structure (or lack thereof) is a double-edged sword. It places Stallone’s thoughtfulness on full display, highlighting the artistic intellect he’s so often denied in the public consciousness. On paper, this framing of the actor as someone with an underrated, underappreciated sense of artistry and emotional depth reads like an exercise in further inflating a Hollywood ego, given his involvement in the film. But in execution, Sly also gives Stallone his long-overdue flowers as a creator of meaningful iconography stemming from an emotionally complicated history.

It’s also cute (and very silly) that, in its final half hour, Sly tries to frame Stallone’s character from The Expendables (whose most recent entry tanked at the box office) as on par with Rocky and Rambo in terms of impact and recognizability. (Do you remember the character’s name? Too bad; the film doesn’t bother to mention it.) This is where it begins to veer off the rails and becomes a re-writing of self-mythology too bold and fictitious to digest. But up until that point, its filmmaking proves deft enough to convince you that we don’t value Stallone’s work in crafting honest and rapturous images nearly as much as we should.

Sly‘s filmmaking tricks work wonders.

Credit: Netflix

Zimny has worked on numerous music videos and concert films (mostly for the legend Bruce Springsteen), and along with co-editor Annie Salsich, he carries forward his penchant for capturing American iconography in rhythmic ways. There’s a propulsive energy to the film’s use of archival footage and photography, which it swiftly intersperses with interviews of Stallone in the present.

At just the right moments, Sly juxtaposes real-life imagery with brief scenes and stills from Stallone’s movies, linking them emotionally and psychologically through quick cuts, as though it were portraying flashes of inspiration. The documentary is as much about a creative person as it is his creative process, and it skillfully creates the illusion of granting secret access to Stallone’s third eye in the moments it turns inward.

Divorced from the knowledge of Stallone’s involvement, Sly is practically revelatory in the way it uses Rocky and Rambo as avenues for the star to psychoanalyze himself. His interviews about his early career are lucid and candid, especially when he expresses the ways in which cinema allows him to garner the adoration he felt he lacked as a child. However, since Stallone is involved at the end of the day, Sly also creates the unavoidable specter of self-promotion.

For instance, his close-up interviews allow him to be vulnerable, but within filmmaking constraints that work against capturing the full scope of this vulnerability. The movie is quick to cut away from Stallone, rather than holding on his confessions. It bobs and weaves while filming him from up close, as though it were a boxer battling him in the ring — a flourish that works counter to the idea these interviews might be a space of comfort, allowing him to open up more completely. There is a lot to process in Sly, much of it worthwhile, but there’s also a looming sense that something is missing.

Sly doesn’t go the distance.

Credit: Netflix

A behind-the-scenes peek such as this one serves to remind viewers just how much like Rocky Balboa Stallone truly is, from his cadence and posture to the way he philosophizes and sermonizes in simple, street-smart ways. However, what separates the two is that while the Rocky movies dig deep into the character at his most flawed and susceptible, Sly is unable (or perhaps unwilling) to do the same.

While a good chunk of its runtime is spent on explaining Stallone’s creation of (and frequent return to) the Rocky and Rambo characters, it truncates the last several decades of his career. Unfortunately, Sly ends up doing the same for his personal life, and the documentary is the weaker for it. Its setups about Stallone using pop artistry as a search for meaning and personal fulfillment end up having few payoffs in the process. Its themes of recursiveness and repetition — Stallone’s frequent return to familiar characters and ideas when new ones don’t work out — simply peters out, rather than revealing any layers to him or coming to a cathartic conclusion.

Worst of all, speeding through Stallone’s life in the 2010s also means reducing the death of his son Sage, who starred alongside him in Rocky V and who has a sizable presence in the documentary via archival footage, to a mere footnote. It’s a part of his story that’s mostly glossed over despite loss becoming a key fixture of his films that would follow, but this is where Stallone’s involvement shows its hand, exposing the limits of self-reflection as a guiding credo for a documentary.

Sage’s death is, understandably, a private and painful subject, as are many of the topics which Sly glosses over, from Stallone’s divorce to his litany of legal issues. Ignoring them calls into question the movie’s own appearance as an intimate sit-down with one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. The film is a journalistic inquiry, but only on Stallone’s terms. It takes what he offers up and spins it into a finely crafted series of montages, but it never pushes further, never asks for more. It is, by nature, a film that is satisfied with its subject’s party line, all but betraying its documentarian spirit in the first place.

Beyond a point, the later stages of his life are reduced to PR talking points with enormous gaps between them. In the process, this can’t help but reframe the rest of the movie too, casting doubt on how much truth (both emotional and factual) the audience had really been made privy to during the preceding runtime. Taken at its word, there’s enough by way of useful reframing of fictitious iconography, and enough by way of the appearance of vulnerability, to make Sly an engaging watch — right up until the point that it isn’t.

Atlassian urges customers to take ‘immediate action’ to protect against data-loss security bug

Australian software giant Atlassian has warned of a critical security flaw that could lead to “significant data loss” for customers, just weeks after state-backed hackers targeted its products. […]