Google and Match announced today they’ve reached a settlement in the antitrust battle Match waged against the tech giant, even as the court case continues with Fortnite maker […]

TikTokkers say their friends aren’t texting back. Why?

Friendship experts explain why friends may not text back and what to do about it.

“Does anybody else have a friend who texts you like they’re famous i.e. they don’t?” asked TikTokker Bel (@khaibellamy) in a video with over 3 million likes and 12 million views.

In the video, Bel goes on to describe how this friend doesn’t reply despite sending them multiple texts and calls — including a joke voicemail about American Idol Season 7 runner-up David Archuleta holding her family hostage. No response.

Bel isn’t alone; the comments on the video are from people on both ends of this, and there are many videos like this on the platform that discuss a lack of communication between friends. Though Bel didn’t respond to Mashable’s request for comment, we spoke to friendship experts about why this happens, and what to do about it.

Why isn’t my friend texting me back?

There are many reasons why someone isn’t communicating, despite what it looks like. “It’s important to acknowledge that what’s tricky is that the symptoms of a friend who doesn’t care and the symptoms of a friend who is not equipped can sometimes look the same,” Bumble for Friends friendship expert Danielle Bayard Jackson told Mashable.

“Not responding is something a person might do if they’re not interested,” she said, “but it’s also something a person might do if they’re overwhelmed, if texting isn’t their thing, if they get anxiety from texting, if they feel frazzled knowing exactly the right thing to say on the spot and respond in a timely manner.”

“Some people find it harder than others to have a balance when they feel overwhelmed with work situations or personal issues, they can easily become disconnected from their phone,” agreed clinical and educational psychologist at E-HEALTH Project, Aura De Los Santos.

Not responding is something a person might do if they’re not interested but it’s also something a person might do if they’re overwhelmed.

Other reasons Jackson cited are that their notifications can be too much; if the friend has social anxiety about saying the right thing; and the potential mental toll of the messages. For example, if you’re sending a string of TikToks, your friend might see it as homework to watch them when they’re busy with something else.

Another example, which you might have used yourself, is asking if they’re free to hang out this weekend. Though it’s a seemingly casual question, the response may not be easy for everyone; for Jackson, she’d have to check her young children’s schedules and coordinate with her husband, which takes time.

“Just because the format of a text is simple, it doesn’t mean the mental labor expected on the receiver’s end is simple,” she said.

It’s also possible that they have trouble responding in a timely manner due to ADHD or another condition; there are many variables within every friendship.

Though convenient, smartphones have engendered a culture where everyone is expected to be available all the time. But contrary to these expectations, friends may not be in a place (physically or emotionally) to instantly respond, said Los Angeles-based psychotherapist Layne Baker. Some friends may just not like texting, Baker continued, and that’s OK. They may have different communication preferences, like enjoying chatting over the phone or FaceTime, or meeting up in-person instead. (As for group chats? That’s a whole different ballgame, and one people might feel other forms of guilt or fatigue from.)

There’s another possibility that could be harder to face, however. It could be true that a friend has stopped texting because their interest is waning or that the relationship is fading. Not responding to messages can be a way to end a friendship without telling the other person, said De Los Santos.

“Sometimes we think that friendships are forever, when this is not the case,” she continued. “One of the parties wants to distance themselves, where they no longer want to have ties with that person, so they don’t take the time to respond and ignore the messages.”

Want more sex and dating stories in your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s new weekly After Dark newsletter.

What should I do if my friend isn’t texting me?

Friendships need to be worked on just like any other relationship, said De Los Santos. Jackson recommends communicating with your friend (try another approach like a different platform, calling, or possibly in person if they’re not responding to texts) and asking what’s best for them. They may not be direct in telling you what’s bothering them; maybe texting overwhelms them, and they just want to see you in person.

Look at your own attachment style as well, Jackson said. Attachment styles don’t just impact romantic relationships! If you’re more anxious leaning, for example, you may text more frequently. Ask yourself what meaning you assign when someone doesn’t text you back, and where that meaning may come from.

“Some of it is on us and our interpretation on the person not getting back,” Jackson continued. “Understanding attachment style helps us manage expectations and recalibrate emotionally.”

Both Jackson and Baker recommend zooming out (figuratively) and “taking a mountain view” of your friendship. Texting is likely just one element of it. Ask yourself:

-

Does your friendship feel healthy otherwise?

-

Does this friend support you?

-

Do you trust them?

-

Is there other tangible evidence that your friend loves you and is invested?

“If the answer is yes, try taking a closer look at why not receiving texts (or texts back) is causing you discomfort,” said Baker. Don’t conflate a lack of response with the notion that they don’t care about you, Jackson added. If you’re really struggling, you could try journaling or seek out a therapist if possible.

In some cases, however, this could be a sign that the friendship has run its course.

“Relationships [need] work, and if you are the only person who writes and tries to get closer, but that friend never makes the effort, you can stop writing and understand that the friendship fulfilled its purpose,” said De Los Santos.

If the friendship isn’t serving you — as in your friend isn’t supportive or doesn’t respect your boundaries, it may be time to end the friendship (we’ve written a guide for you if it comes to that). A friendship breakup can be just as devastating (if not more) than a romantic one; here’s how to cope with a friendship ending, if it comes to that.

It’s understandable to want a text back. These days, that may be the primary way of communicating with your friend. But know there are a multitude of explanations why — and this may be better talked out IRL.

Meta rejected Unbound’s sex toy ads — until they marketed to men

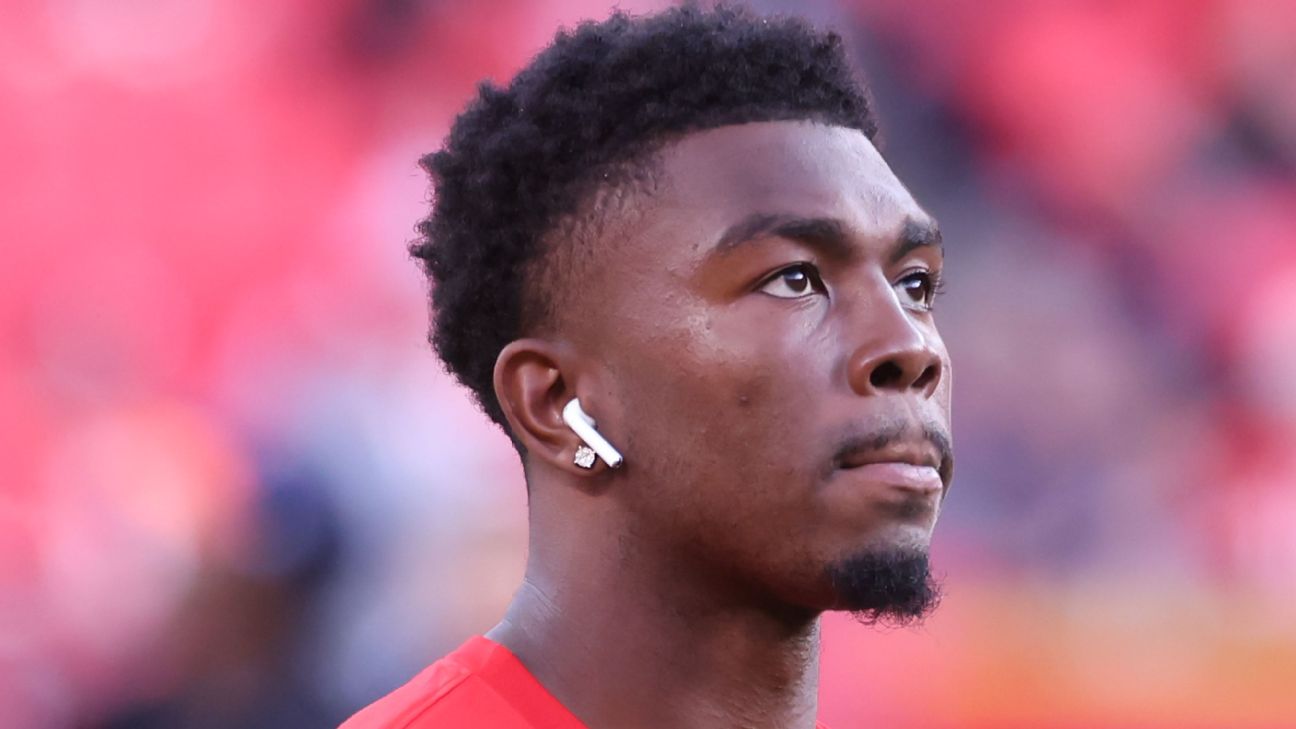

Sexual wellness brand Unbound made ads for a fake male-focused company, Thunderthrust. Meta approved Thunderthrust’s ads.

For years, online and offline spaces have rejected ads for products to help make sex better for women — but approved ones for men. In 2019, sex toy brand Dame sued the MTA over rejected subway ads (which they eventually settled). That same year, Dame and fellow brand Unbound pointed out this discrepancy with a quiz on what ads are blocked versus which are approved. When the ad centers a women’s sex toy, it’s rejected; when it’s about an erectile dysfunction product, it’s approved.

It’s sad to say that in 2023, the case is still the same. Now, Unbound tested whether Meta would approve its product ads if they were targeted to men — and it did.

When Unbound submitted ads for products like its Ollie wand vibrator, Bandit cock ring, or Cuffies handcuffs as they are, Meta rejected them. These ads feature the bright-colored products alone or with hands, usually in front of a colorful or sky backdrop.

“We want as many people as possible to have the best sex possible,” Unbound’s CEO and co-founder Polly Rodriguez said in a video on Twitter. “But the problem is that we cannot reach them.”

Unbound’s senior content manager Maddy Siriouthay went on to explain that many advertising platforms write their compliance policies through the lens of family planning — products that assist or prevent pregnancy. Here is a snippet from Meta’s Adult Product or Services ad policy:

Ads must not promote the sale or use of adult products or services. Ads promoting sexual and reproductive health products or services, like contraception and family planning, must be targeted to people 18 years or older and must not focus on sexual pleasure.

In practice, however, Unbound found a plethora of ads to improve erectile dysfunction and “male” sexual performance. Some of these ads contained explicit language and body parts.

As an experiment, Unbound edited their products to be in stereotypical dude colors (gray), changed the target audience, and created a name for a fake male fitness and performance enhancing company, Thunderthrust. The toys themselves stayed the same, and Unbound submitted Thunderthrust ads for approval.

Credit: Unbound

Credit: Unbound

Meta approved these male-targeted ads.

This is a long-standing problem that companies like Unbound are fighting against. Earlier this year, these brands along with the Center for Intimacy Justice filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) requesting that the FTC take action against Meta’s rejection of female-focused ads. This comes after Meta’s policy change in October 2022 to allow sexual health, wellness, and reproductive health ads — but, judging from this experiment, there’s still more to be done.

The Center has an ongoing petition to #StopCensoringSexualHealth, which Unbound workers encourage people to sign in its Thunderthrust videos.

“These policies are discriminatory in the way they are written, because they only allow one gender identity access to the tools and information that support a holistic definition of sexual wellness,” said Rodriguez in a second Twitter video.

Want more sex and dating stories in your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s new weekly After Dark newsletter.

“We’d love to talk to Meta about improving the policies so that they are less gendered in how they are written and applied, and we’d welcome any conversation at any point in time,” Rodriguez told Mashable, while commenting that Meta has historically not been willing to come to the table.

Mashable reached out to Meta for comment and will update this story if received.

“Vibrator ads might seem a tedious hill to die on,” said Siriouthay in Unbound’s video, “but companies like Meta which own social media networks like Facebook and Instagram have major influence in what we see every day, which can then influence our subconscious beliefs, and the choices we make, and the opportunities we have.”

Does it matter if Taylor Swift is a girl’s girl?

What is a girl’s girl? Is Taylor Swift a girl’s girl? Does the girl’s girl trope stem from internalized misogyny?

Have you been called a “girl’s girl” yet? If pop culture is any proof, winning the title of girl’s girl is quickly emerging as the highest level of a compliment. So what exactly is a girl’s girl? She checks on you at a party. She holds your hair back when you’re sick. You can depend on her to be honest with you if your partner is cheating. She’ll never hate you for how you look and will always tell you if there’s something in your teeth. She’s your absolute ride or die. Side note: she exists in a primarily heteronormative society.

On TikTok the hashtag #GirlsGirl has 646 million views, but the phrase isn’t just ubiquitous online. IRL too, celebrities (and celeb-adjacents) have been throwing the term around. But, what does it really mean? And does it really matter if we don’t fit the girl’s girl bill?

Recently, in a cover interview with Variety, Ice Spice told the magazine that many rappers pretend to be girls’ girls. “People want to be all ‘I’m a girl’s girl,’ but then behind the scenes being bitches. I feel like the competition is what keeps us all excited because I think we all secretly enjoy competing and seeing who puts that shit on better and who’s gon’ get the most views,” the singer said.

At the tail end of September, when rumors of Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce dating first surfaced, Kelce’s ex Maya Benberry told the Daily Mail that the footballer had cheated on her. In an attempt to warn Swift, Benberry added, “Taylor seems like such a fun girl with a beautiful spirit so I wish her the best of luck but I wouldn’t be a girls’ girl if I didn’t advise her to be smart.” This is hardly the first time that the term girl’s girl was used in the context of a celebrity relationship.

In July 2023, when the unverified rumors and blind items of Ariana Grande and her Wicked co-star Ethan Slater allegedly dating first emerged, Slater’s estranged wife Lilly Jay told Page Six, “[Ariana’s] the story really. Not a girl’s girl. My family is just collateral damage.” This comment stirred chaos on the internet; several fans posted videos theorizing about why Grande isn’t a ‘girl’s girl’. In some ways, this glorified use of the girl’s girl phrase feeds into the patriarchal system that vilifies women, making them the sole bearer of blame while absolving men of any responsibility. The shame and scrutiny that Grande faced was grossly disproportionate to Slater.

Clearly, there’s a lot of pressure to be seen as a girl’s girl and flak abounds when you appear to fail to do so correctly. But why does it matter?

“Throughout popular culture, women and girls are positioned as being in ‘competition’ with one another.”

At its core, being a girl’s girl means being a reliable friend, someone you can count on for honesty and support. You may wonder: doesn’t this just mean being a decent person? For the most part yes, but there’s a reason why the category is gaining steam in the present day. Think back to the early 2000s when trends demanded women denounce their femininity. The cool girl – who loved hanging out with the boys and hated pink – ruled the zeitgeist. Today the internet calls this person the “pick me” girl: she thrives on being different (read: better) from other girls and seeks male validation. According to Dr. Amelia Morris — lecturer in media and communications at the University of Exeter who studies the relationship between pop culture and socio economic imbalances — this system of women being pitted against each other forms the fabric of a heteronormative society.

“Throughout popular culture, women and girls are positioned as being in ‘competition’ with one another…The term ‘bitchy’ is itself inextricably gendered, conflating femininity with malice (see the plethora of online articles advising parents on how ‘not to raise bitchy girls’), whilst it is assumed that men enjoy ‘relaxed’ and ‘easy going’ relationships,” Morris explains. In contrast, the 2020s are (so far) a decade of peak girlification. Greta Gerwig’s Barbie brought pink and hyper-femme solidarity to the forefront while online trends like girl dinner, hot girl walk and girl math position similarities among women as a celebration.

“Within the heteronormative context the term ‘girl’s girl’ speaks to a femme solidarity that recognises platonic friendships as being as important as a romantic partner, creating space for navigating life under patriarchal capitalism,” Morris says. Today, nothing is cooler than hanging out with your girlies. Guides on TikTok tell you how to reach this cult status while other creators warn you of people pretending to be supportive: they behave differently in front of men, point out your insecurities, or greet your boyfriend before they greet you.

Are girls’ girls actually becoming bullies?

In a video, TikToker Kelly Kim says if an acquaintance adds your love interest to their close friends list within 48 hours of meeting them, they are not a girl’s girl and “have to go”. She tells Mashable, “At the start of the trend, if someone said they were a girl’s girl I instantly trusted them more, it made them more approachable. But now, the phrase has become an easy way to talk about someone who isn’t a girl’s girl and who you should be wary of.”

Another post with the caption “girl’s girls 101” shames women for saying that they’re hot and have their shit together. In the video, the creator said “in the kindest way possible, it’s the most pick me shit ever.” This is where the categorisation gets tricky. In theory being a “girl’s girl” is positive: it’s women supporting women. But it also leaves a vast gap in defining what a supportive woman looks like, especially when digital cultures are so diverse and include different understandings of solidarity.

As the term gains popularity, it’s being weaponized to condemn women for not fitting a rigid, often arbitrary idea of what a “girl’s girl” should look like – as in the case of Ariana Grande and the hate that was unleashed in the wake of the unverified rumors or the TikTok videos that slut shame women. In positioning itself as an antithesis to the “pick me” girl, the “girl’s girl” trend sets itself up for failure. Through overwhelming patterns of “othering” and looking down upon a certain brand of women, the trend embroils itself in the very misogyny that it was hoping to dismantle.

Psychologist Eloise Skinner explains, “The phrase is being used to pull apart women who behave in a way that is considered to be the opposite of the ‘girl’s girl’ whether that’s wanting male attention, disassociating themselves from traditionally ‘girly’ traits or being competitive with other girls. This can leave women feeling isolated and shamed.”

The impact of internalized misogyny

Using the phrase also exerts a certain amount of pressure and responsibility to return the favor.

For instance, Benberry publicly warning Swift under the guise of being a girl’s girl also lays a liability on the singer. It leaves the ball in her court suggesting that a fellow girl’s girl would never date a man who has treated another woman “poorly” – however this is defined.

Through her decades-long career, Swift has been seen as a girl’s girl (think of the early squad), criticized for being one (think of how White the squad was) and been relentlessly slut shamed, so much so that she’s written songs about it. Still, every time Swift allegedly dated a controversial man (Matty Healy), the blame impacted her disproportionately.

Similarly, while Grande and Slater are consenting adults, popular media has placed the onus of the relationship on Grande alone, holding her accountable for the end of Slater’s marriage as well as her own. Flag bearers of the ‘girl’s girl’ trend that hold women to unrealistic standards contribute to this bias.

“Some aspects of the ‘girl’s girl’ trend (such as women not ‘knowing/realizing’ that they are attractive) is reflective of the virgin/whore dichotomy, wherein women have historically been positioned as either ‘good’ (read: sexually ‘pure’ and modest) or ‘bad’ (sexually ‘promiscuous’ and self-assured, particularly regarding their appearance),” explains Morris. This internalized misogyny seems to shape the shame and guilt that some girl’s girls use in their critique of other women.

But instead of canceling the girl’s girl’ or placing it on a moral pedestal, the trend – just like countless others – should be viewed with nuance. In the face of everything that’s wrong with the world, romanticizing female friendships, having snacks for dinner or going on long walks is a welcome relief. It should be seen as just that, a momentary, feel-good trend, not an instructive, idolized cult.

“We’re constantly encouraged to define, identify and project ourselves so it’s not surprising that a trend based on categorisation of behavior is popular,” says Skinner. “It’s important to remember, though, that we’re all much more complex and nuanced than a minute-long TikTok video would allow us to capture, and we should prioritize figuring out who we are (away from the public lens of social media, perhaps), and allowing others the space to do the same.”

‘Fingernails’ review: A sci-fi love triangle that fumbles its own potential

Jessie Buckley, Riz Ahmed, and Jeremy Allen White star in “Fingernails,” which introduces a test that tells you if you’re in love. Review.

What would you do if a test determined that you and your partner were completely, irrefutably, 100% in love? Would you sit back, content in the relationship you’ve already built? Or would you keep working at it? The tension between those two options lies at the heart of director Christos Nikou’s Fingernails, which stars the buzzy trio of Jessie Buckley, Riz Ahmed, and Jeremy Allen White.

Set in a future where love can be tested and quantified, Fingernails examines how total certainty in a relationship can be its own undoing. That’s a big question to consider, but unfortunately, the film doesn’t rise to the occasion to interrogate it in any particular depth. Instead, Fingernails finds itself on an all-too predictable route, albeit one that’s enjoyable enough thanks to three strong lead performances and some charming retro-futuristic sci-fi flair.

What’s Fingernails about?

Credit: Apple TV+

Fingernails takes place in a world just like our own, except for one key difference: Couples can take a scientific test to find out if they are actually in love. The certainty of the test has caused divorce rates to plummet, but it’s also created a new tension within budding romances. How can you know if your feelings are real if a machine can just tell you whether you’re 100% or 0% in love? (Worse is the dreaded 50% result, where only one member of the couple is in love, but the test can’t tell which.)

To supposedly strengthen their relationships and ensure they pass the test, couples attend classes at the Love Institute. There, instructors guide them through a series of exercises, which range from playing competitive sports together to giving yourself an electric shock when your partner leaves the room. Nothing says love like Pavlovian conditioning!

Anna (Jessie Buckley) is a new instructor at the Love Institute. She’s joined the project to understand more about love and the ways in which the exercises help people connect further. In theory, Anna shouldn’t need to do any of this. Three years ago, she and her boyfriend Ryan (Jeremy Allen White) received a positive test; surely that’s enough to set them up for a lifetime of loving bliss, right? Wrong.

It’s clear right from the get-go that the two are stuck in a rut. Ryan, who is essentially a shrug in human form, finds peace in the routine, thinking that outside confirmation of his and Anna’s love means they don’t have to change anything about their relationship. Meanwhile, Anna wants to work on their connection every day. She tries to introduce spontaneity into their relationship in the form of modified Love Institute exercises, but she’s clearly worried about what Ryan will think, to the point that she lies to him about even working at the Institute at all.

Enter Amir (Riz Ahmed), Anna’s mentor and instructor at the Institute. He’s everything Ryan is not: devoted to the Love Institute and to bringing couples closer together. He devises several of the Institute’s most out-there experiments, including trying to fake a movie theater fire during a Hugh Grant retrospective in order to get couples to save each other’s lives. The more time he and Anna spend working together, the more she begins to sense that he’s what she’s missing in her life. But what do her newfound feelings mean for her relationship with Ryan, or for her trust in the test?

Fingernails is soft sci-fi that doesn’t go deep enough.

Credit: Apple TV+

With its love triangle firmly in place, Fingernails sets off exploring what Anna will choose. Will she remain in the comfort of the seemingly confirmed love she has with Ryan, or risk acting on the burgeoning attraction she feels for Amir?

The path Fingernails ends up taking proves dismayingly straightforward. There’s little examination of Ryan’s complacency — he’s as good as a background character, despite White’s grounded performance. (The same goes for a highly underutilized Annie Murphy as Amir’s partner Natasha.) Meanwhile, the connection between Amir and Anna feels entirely too familiar and frankly, too underdeveloped. “Watching a love story feels safe. Being in love doesn’t,” Amir tells Anna after a screening of Notting Hill. Yet their relationship, built on lingering stares and fumbling meet-cutes, is as safe as you can get, even with all the sci-fi love testing Nikou throws at it.

The testing itself, and its implications for the wider world, do result in some of the movie’s most impactful moments. To take the love test, an instructor has to tear one of your fingernails off, meaning couples have to painfully lose part of themselves in order to know if they’re meant to be (at least by testing standards). You can instantly recognize someone who’s taken the test by the bandage wrapped around their finger, a visual shorthand that leads to some awkward questions, as more people inevitably test negative than positive. Elsewhere, details like a radio station that only plays songs dedicated to partners who break up after unsuccessful tests add further melancholy to Anna’s surroundings. After all, she’s one of the lucky ones who’s found true love — would it be wrong to give it up, given the pain the test has brought so many other couples?

The Love Institute also proves to be a fascinating environment. Headed by self-styled love expert Duncan (Luke Wilson), the Institute is rendered in twee fashion, with autumnal red walls, a soundtrack of falling rain meant to evoke romance, and whimsical maquettes laying out its upcoming exercises. The exercise sequences are Fingernails at its funniest, and sometimes its most tragic. Blindfolded sniff tests, French-language karaoke, and even skydiving are meant to heighten love and trust, but does anyone involved in the creation of these exercises really know what they’re doing? Or are they just blindly looking for love in the dark? After all, Anna and Amir can appear as lost or as desperate as their clients when it comes to love.

Take Rob and Sally (Christian Meer and Amanda Arcuri), a couple of 21-year-olds at the Institute to strengthen their bond. Anna gloms onto them almost instantly, attaching her own self-worth and romantic desires to their success. It helps that Rob resembles a younger version of Ryan; perhaps Anna sees herself in this couple, and deeply wants to recapture the beginning stages of her and Ryan’s relationship? Yet Fingernails doesn’t examine these similarities much further. Nor does it probe the biggest downside of the test — the stagnancy a positive result can provoke in couples — beyond simply acknowledging that it exists.

For their parts, Buckley and Ahmed have a charming rapport. There’s an aching sadness to both performances as well, although Fingernails doesn’t focus too hard on the root of that sadness. There’s little effort to talk through and acknowledge relationship issues after a positive test, or the loneliness negative test after negative test can provoke. Instead, the film suggests that finding a shiny new person — perhaps even projecting your own romantic ideals onto them — is the best solution to your relationship woes. It’s a frustrating approach to a genuinely interesting sci-fi concept, one that simply scratches the surface of its own potential instead of digging deeper.

Fingernails hits select theaters Oct. 27, and will stream on Apple TV+ Nov. 3.

Relationship community app Keepler wants to guide you through your dating journey

Keepler, a new app for daters to receive expert advice, officially launched today to give users the skills and guidance to confidently navigate the dating scene or improve […]