A new report from Amnesty International accuses Meta of having an inciting role in an ongoing conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, pressuring the company to compensate victims and reform its content moderation.

Meta, and its platform Facebook, are facing continued calls for accountability and reparations following accusations that its platforms can exacerbate violent global conflicts.

The latest push comes in the form of a new report by human rights organization Amnesty International, which looked into Meta’s content moderation policies during the beginnings of an ongoing conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region and the company’s failure to respond to civil society actors calling for action before and during the conflict.

Released on Oct. 30, the report — titled “A Death Sentence For My Father”: Meta’s Contribution To Human Rights Abuses in Northern Ethiopia — narrows in on the social media mechanisms behind the Ethiopian armed civil conflict and ethnic cleansing that broke out in the northern part of the country in Nov. 2020. More than 600,000 civilians were killed by battling forces aligned with Ethiopia’s federal government and those aligned with regional governments. The civil war later spread to the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions, during which time Amnesty International and other organizations documented war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the displacement of thousands of Ethiopians.

“During the conflict, Facebook (owned by Meta) in Ethiopia became awash with content inciting violence and advocating hatred,” writes Amnesty international. “Content targeting the Tigrayan community was particularly pronounced, with the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, pro-government activists, as well as government-aligned news pages posting content advocating hate that incited violence and discrimination against the Tigrayan community.”

The organization argues that Meta’s “surveillance-based business model” and algorithm, which “privileges ‘engagement’ at all costs” and relies on harvesting, analyzing, and profiting from people’s data, led to the rapid dissemination of hate-filled posts. A recent report by the UN-appointed International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE) also noted the prevalence of online hate speech that stoked tension and violence.

Amnesty International has made similar accusations of the company for its role in the targeted attacks, murder, and displacement of Myanmar’s Rohingya community, and claims that corporate entities like Meta have a legal obligation to protect human rights and exercise due diligence under international law.

In 2022, victims of the Ethiopian war filed a lawsuit against Meta for its role in allowing inflammatory posts to remain on its social platform during the active conflict, based on an investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Observer. The petitioners allege that Facebook’s recommendations systems amplified hateful and violent posts and allowed users to post content inciting violence, despite being aware that it was fueling regional tensions. Some also allege that such posts led to the targeting and deaths of individuals directly.

Filed in Kenya, where Meta’s sub-Saharan African operations are based, the lawsuit is supported by Amnesty International and six other organizations, and calls on the company to establish a $1.3 billion fund (or 200 billion Kenyan shillings) to compensate victims of hate and violence on Facebook.

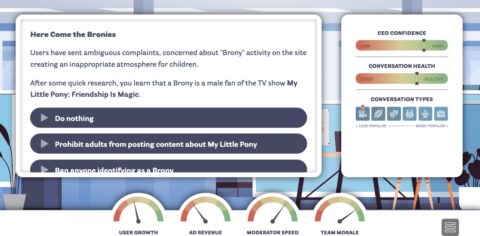

In addition to the reparations-based fund, Amnesty International is also calling for Meta to expand its content moderation and language capabilities in Ethiopia, as well as a public acknowledgment and apology for contributing to human rights abuses during the war, as outlined in its recent report.

The organization’s broader recommendations also include the incorporation of human rights impact assessments in the development of new AI and algorithms, an investment in local language resources for global communities at risk, and the introduction of more “friction measures” — or site design that makes the sharing of content more difficult, like limits on resharing, message forwarding, and group sizes.

Meta has previously faced criticism for allowing unchecked hate speech, misinformation, and disinformation to spread on its algorithm-based platforms, most notably during the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections. In 2022, the company established a Special Operations Center to combat the spread of misinformation, remove hate speech, and block content that incited violence on its platforms during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It’s deployed other privacy and security tools in regions of conflict before, including a profile lockdown tool for users in Afghanistan launched in 2021.

Additionally, the company has recently come under fire for excessive moderation, or “shadow-banning”, of accounts sharing information during the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, as well as fostering harmful stereotypes of Palestinians through inaccurate translations.

Amid ongoing conflicts around the world, including continued violence in Ethiopia, human rights advocates want to see tech companies doing more to address the quick dissemination of hate-filled posts and misinformation.

“The unregulated development of Big Tech has resulted in grave human rights consequences around the world,” Amnesty International writes. “There can be no doubt that Meta’s algorithms are capable of harming societies across the world by promoting content that advocates hatred and which incites violence and discrimination, which disproportionately impacts already marginalized communities.”